Sunday 2 September 1666: Fire breaks out in London

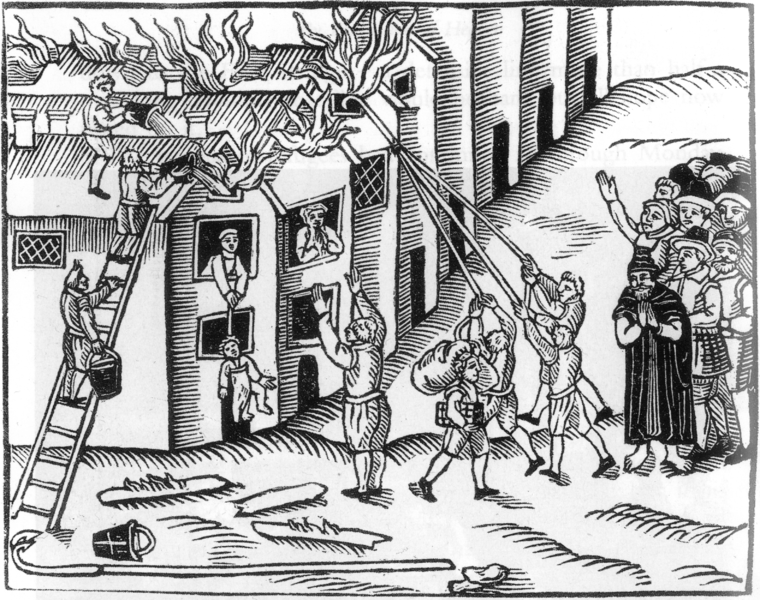

355 years ago today, Samuel Pepys was woken by Jane, one of his maids, at 3 o’clock in the morning. Pepys was no stranger to nocturnal liaisons with the staff, but this was no time for a fumble. Jane had seen ‘a great fire’ close to London Bridge and she was worried enough to wake her master. Pepys pulled on a nightgown, went to his window and saw the fire, but little troubled he ‘thought it far enough off, and so went bed again and to sleep’. His initial insouciance was more common than we might think. On first hearing news of the fire, Sir Thomas Bloodworth, the Lord Mayor of London, is said to have exclaimed ‘pish! A woman might piss it out’. This might seem strange to us, but the fact is that fires – often very serious – had always been something a commonplace in London. How could they not be? Most houses and shops not only had open fires within, they were also made of combustible wood and thatch. Although plague had carried off 100,000 Londoners in the preceding year, the city’s population was still some five times bigger than it had been a century before, forcing more and more Londoners to live in dangerous, overcrowded conditions. Fire prevention and control measures were rudimentary at best: there were no smoke alarms, extinguishers and sprinkler systems in pre-modern London. Instead, the citizens relied on buckets and hand-squirts to apply water, and fire-hooks to pull down burning buildings so that they could then smother the flames. This is not to say that no one cared about fire. On the contrary, it was an ever-present concern of the authorities in London. At this stage, however, there seemed no reason to think that this fire, which had broken out in a baker’s in Pudding Lane and which, so far at least, had spread only to a few neighbouring houses, would be more serious than any other of recent time.

Four hours later, things were looking a good deal worse. Londoners told each other that 300 houses had already been destroyed, and the streets were filled with desperate citizens, laden with their possessions, heading for the river or for the narrow gates in the city’s defunct walls. It had been a hot, dry summer and London’s wooden buildings were like tinder. Worse, and unusually, the wind was blowing from the east driving the fire, now perhaps a conflagration, west towards Thames Street. This was a worrying development. As Pepys noted, the houses and warehouses there were ‘full of matter for burning, as pitch and tar’, as well as ‘oyle and wines and Brandy and other things’, such as coal and timber. Once the sparks and flames had touched these properties, it took no more than an hour for the fire to reach the Steelyard, where London’s Cannon Street station now stands.

At Whitehall, King Charles II and his brother James, Duke of York, discussed how best to react to the developing crisis. On Pepys’s advice, they commanded the Lord Mayor of London ‘to spare no houses but to pull down before the fire every way.’ This was no easy decision to make. Pulling down burning houses was one thing, but to destroy property as yet untouched by fire, in order to create firebreaks which would save the houses of others, well, that was something quite different. Few affected homeowners would be happy with that and, should the fire soon die out, there would be expensive compensation bills to pay. These concerns weighed heavy with the king, but he ordered Pepys to convey his command to the Lord Mayor all the same. By the time Pepys found Bloodworth in Cannon Street, around midday, he already looked ‘like a man spent’. Houses were being pulled down, Bloodworth cried, but not quickly enough and the fire continued to spread fast.

For the rest of the day, the wind pushed the fire, by now out of all control, west and north. The king and his brother came down to London by barge, but so crowded was the river with boats engaged in rescue missions, that they struggled even to navigate a way through to the city. Towards the end of the day, having been in the city and St James’s, and having been driven off the river by the smoke and heat, from a tavern on London’s south bank Pepys observed that the fire formed an arch ‘above a mile long’ across London, with churches and houses all ablaze, cracking and falling apart. It made him weep to see it. How on earth could this inferno be tamed?

Ian Stone, historian | Monday 3 September 1666: London ablaze

3rd September 2021 at 7:01 am[…] Sunday 2 September 1666: Fire breaks out in London […]