Finding the Traces of London’s Huguenots

Angers is a pretty, prosperous city in the province formerly known as Anjou in western France. Unlike Cologne, Antwerp or Amsterdam, it is not a city which one immediately connects with the history of London. True, for a brief period in the Middle Ages, three kings of England, Henry II, Richard I and John were also the counts of Anjou, but there is little evidence that this dynastic union brought the Londoners and Angevins particularly close together. Certainly, once John had lost the territory of Anjou, along with Normandy and Poitou, to Philip Augustus of France in 1202-4, no one could argue that the citizens of London and Angers had very much to do with each other at all. There is, however, a building in Angers called the Logis Barrault which does have a very important connection with the history of London.

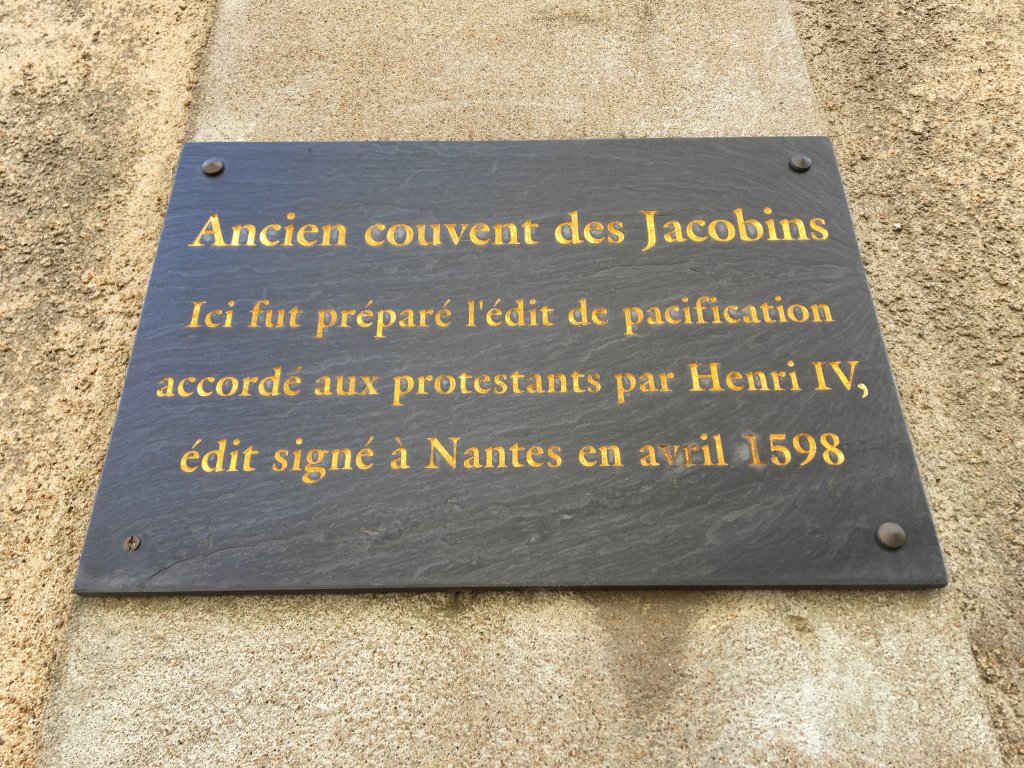

In that building, in March 1598, King Henry IV of France drew up an edit (a royal edict) de pacification which sought to end France’s bloody wars of religion. These wars had been fought more or else continuously since 1562, claiming perhaps three million lives. One month later, the king issued letters patent at Nantes which gave legal effect to the edit. At that point, it became known as the édit de Nantes (Edict of Nantes).

The Edict of Nantes granted limited religious toleration to French Protestants, commonly known as Huguenots. It thus ended France’s wars of religion. The steps taken in the Logis Barrault, then, were of profound importance in European history. After Henry IV’s death, however, religious and political tensions rose between the Huguenots and the Catholic majority in France. In the end, Henry’s grandson, King Louis XIV of France (1643-1715), decided to revoke the Edict of Nantes. Therefore, on 22 October 1685, he issued the Edict of Fontainebleau. Under the terms of this revocation, all standing Protestant churches in France were to be pulled down, all Protestant schools were to close, Protestant worship was forbidden and Protestant priests were banished from France. The Edict of Fontainebleau expressly forbad emigration by Huguenots. Nevertheless, it is clear that hundreds of thousands did leave France, fleeing to the Netherlands, territories in the Holy Roman Empire, Switzerland and even the Dutch Cape Colony (now South Africa). In addition, many made their way to England.

The majority of those who came to England settled in London. While there is no way of knowing exactly how many Huguenots came to the city, they must have numbered in the tens of thousands. There were as many as fourteen churches in Soho, in London’s expanding west end, catering for the religious needs of this French community, one of which, the French Protestant Church of London in Soho Square, is still standing. Several men of Huguenot descent were among the founder directors of the Bank of England. Sir Theodore Janssen (c.1658-1748) settled in London in 1683. In 1694, when the Bank of England was established, he was one of its founder members and was one of only twelve men to invest £10,000 in the new venture. Sir John Houblon (1632-172), who had been born to a family of French Protestants long-established in London, was a successful merchant who was chosen to be the Bank’s first governor by his fellow subscribers to the incorporation. He held that post from 1694 to 1697. His brother, Abraham, served as governor from 1703 to 1705. Another brother, James, was also one of the founding directors of the Bank. These men played a role in England’s political life, too. Janssen sat as MP for Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight from 1717 until 1721. John and James Houblon both held office in London as common councilmen and alderman. John was elected as lord mayor in 1695, James as MP for the City of London in 1698. These men were also famed for their urbanity. Janssen, whose library in 1721 contained more than 560 volumes, covered three-fifths of the cost of the of the publication of Suidas’s Greek-Latin lexicon with the newly-established Cambridge University Press. Samuel Pepys delighted in the company of the Houblon brothers. On the 9 February 1666 he dined with them ‘til about 11 at night, with great pleasure; and a fine sight to see these five brothers thus loving one to another, and all industrious merchants.’ Pepys was especially fond of James Houblon, ‘a man I love mightily’, and the two men became the best of friends.

But the impact of Huguenot immigration was not just felt at the top of society. Huguenot artisans had skills which improved the manufacture of mechanical objects such as watches, guns and clocks. For neither the first nor the last time, French fashions came into England, and the production of wigs, shoes and fans was enhanced by Huguenot talent. In Wandsworth, which was then a settlement outside London to the south-west, Huguenot craftsmen established a felt hat industry. In modern Wandsworth stands a Huguenot Cemetery in Huguenot Place. Nowhere, however, was the impact of the arrival of the Huguenots more visible than in Spitalfields in London’s east end. Daniel Defoe was born in 1660 and he remembered Spitalfields as a field with cattle feeding upon the grass. In 1724, Defoe described Spitalfields as an industrial suburb, home to over 200,000 people. The single most important industry in this area was silk-weaving. By 1750, 500 master weavers and 15,000 looms were clustered around Spital Square. Perhaps as many as one in four local residents were dependent upon silk manufacture for their livelihoods. The silk industry was dominated by Huguenot merchants and artisans.

Many merchants and retailers profited handsomely from trade in silk produced in the area. Peter Ogier, a Huguenot silk merchant, built a townhouse on Spital Square, in or shortly after 1740. Now 37 Spital Square, it is the square’s only surviving Georgian townhouse and home to the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

Those interested in experiencing what life in a house such as this might have been like, should visit Dennis Severs’ House, around the corner in Folgate Street, which recreates the home of a family of eighteenth-century Huguenot silk weavers.

Just a stone’s throw from here. the two houses at 56-58 Artillery Lane, which were built in the eighteenth century by Sir Robert Taylor, were home to Huguenot silk merchants. Their large windows, designed to showcase their wares, remind us that this was also the age when retail shops really began to establish themselves in London.

The French influence is visible everywhere in Spitalfields in the names of the streets also. Fleur de Lis Street and Nantes Passage need no explanation.

John Calvin (1509-64), the French lawyer, theologian and reformer, who more than anyone else led the Reformation in France and Switzerland, is remembered in Calvin Street. George Fournier was a Huguenot refugee who gave his name to Fournier Street, the best-preserved eighteenth-century street in the area.

At the end of Fournier Street, where it meets Brick Lane, stands the Jamme Masjid, a mosque which now caters for the local Bangladeshi population. However, the building was originally a Huguenot chapel, which was built in 1743-44. It was subsequently converted into a synagogue in 1897, before becoming a mosque in 1976. This one building epitomises better than any other the history of migration in this part of London.

Should one head north on Brick Lane and cross Bethnal Green Road to head into Shoreditch, the Huguenot influence is just as visible. La Rochelle in France was perhaps the most important centre for Protestantism in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century France. Its importance to the London Huguenots is remembered in Rochelle Street, now part of the Boundary Street estate. Also a part of the estate are Camlet Street, Montclare Street, Navarre Street – King Henry IV of France was King Henry of Navarre before he ascended to the French throne – Calvert Avenue, Ligonier Street and Palissey Street, all of which, too, reflect the Huguenots’ historic presence in the area.

In both Spitalfields and Whitechapel, one can also find streets with tenter in the name, tenters being frames on which wet cloths were stretched and left to dry.

The Spitalfields’ silk industry has long since disappeared. In the nineteenth century London’s silk weavers were unable to compete with cheaper silks, whether produced in the north of England, in towns such as Macclesfield, or overseas. The traces of the industry, and of the Huguenots who worked within it, are, however, still there for us to see. Of course, no one could have imagined the industry’s rise and decline in the Logis Barrault in Angers in March 1598. At that time, King Henry IV, one of the most far-sighted men ever to have sat on the French throne, wished only to bring to a close some of the most vicious confessional warfare that had been seen in sixteenth-century Europe. Had the religious toleration which he envisaged in the Edict of Pacification and proclaimed in the Edict of Nantes been maintained, then there would have been no Huguenot exodus to London. London’s silk industry would perhaps never have established itself in Spitalfields in the way that it did. The creation of the Bank of England, in 1694, would have looked very different too. In fact, it is, at least on one level, paradoxical that so many of the original directors of the Bank of England, an institution established to finance war with France, were of French descent. It is difficult not to conclude that, when it comes to the Huguenots, la perte de la France fut le gain de Londres.

Richard Shepley

1st November 2019 at 6:08 pmGreat article.You don’t mention any resistance to this massive influx of foreigners into London, yet surely there must have been some?

Ian Stone

7th November 2019 at 3:28 pmThank you Richard.

I’m not sure there was actually much hostility towards the Huguenots at the time. Certainly, there isn’t much evidence of that. Pepys obviously felt great affection for the Houblon brothers. I think many Londoners felt sorry for their fellow Protestants. At the time Londoners looked at France and saw a Catholic, tyrannical king (Louis XIV) who, given the chance, would invade England and reduce them to a similar status of subjection and enforce ‘popery’. More than anything I think they felt an obligation to help their co-religionists and they saw the Huguenots’ experience as a warning of the threat which they themselves faced.

Terry Beaubois

25th March 2022 at 7:16 pmMy ancestor was a Huguenot who fled France in the 1690’s and went to England. He was somehow offered land in the English colony of Virginia and continued to the New World. After many years, descendants of the French Huguenot, ended up in Michigan, where my father was born. Researching our family’s ancestry has provided this information. My next visit to London will include visits to the areas and building mentioned in this article. It adds interesting related information to my family’s history.