The Restoration of Canterbury Cathedral

‘While Thomas lives you will have neither peace nor quiet nor see good days’. We know not who supposedly uttered these words to King Henry II (1154-89) about his troublesome archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket (d. 1170), but whoever it was, they had arguably more perspicacity than the two protagonists themselves. Henry was one of England’s greatest monarchs. He was a man filled with seemingly boundless energy, a man who, almost through force of will, held together a polity which stretched from Hadrian’s Wall to the Pyrenees, and a man whose administrative reforms have seen him lauded as the king who did more to establish the English common law system than any before or since. He was also possessed of a fearsome Angevin temper. Becket, on the other hand, was the son of a London merchant who through Henry’s patronage rose to become royal chancellor and then Archbishop of Canterbury. He was ambitious and likeable, but stubborn, inflexible and self-important. Their famous quarrel was, in the words of Wilfrid Warren, ‘a classic tragedy – the story of heroic men with remarkable qualities, undone by equally great flaws of character, flaws of passion and of pride.’

In the end, their clash was brought to an end following an outburst of Henry’s rage and of Thomas’s refusal to bend. In the late afternoon of 29 December 1170, in the cathedral of Christ Church at Canterbury, four knights, who believed themselves to be acting on Henry’s orders, hacked Becket to death. The murder shocked Christendom. We might imagine the Middle Ages to have been an especially bloody period, but the slaughter of an archbishop in his own cathedral appalled contemporaries across Europe. A little more than two years after his death, Becket was canonised. Medieval Londoners were quick to adopt Thomas, a son of the city who styled himself as ‘Thomas of London’ on his first seal, as their patron saint. The chapel which stood on London Bridge was dedicated to his memory and an image of Becket enthroned subsequently appeared on the city’s own seal.

On the circumference of this seal was inscribed the injunction ‘may thou never cease, O Thomas, to protect me who gave thee birth’. Almost immediately pilgrims began to make the journey from London to the site of Becket’s ‘martyrdom’, a phenomenon best known to us through Geoffrey Chaucer’s famous Canterbury Tales.

The cathedral wherein Becket was murdered was not the one we see today. It was, rather, a Romanesque church which had been raised by Archbishop Lanfranc (1010-89) in an astonishingly quick period of just seven years (1070-77). In 1174, however, the choir of this cathedral, along with the monastic infirmary and the chapel of St Mary, were devastated by fire. The new cathedral was redesigned as a more fitting shrine for the cult of Thomas Becket, and at least some of the expense involved in its rebuilding could be met with money raised from the pilgrims travelling to Becket’s shrine. The monks at Canterbury chose William of Sens as chief mason for the reconstruction on account of ‘his lively genius and worthy fame’. They had their man right. William’s design was revolutionary at the time. He used contrasting stone to add colour and texture to the structure, a technique which is perhaps at its most effective in the Trinity Chapel at the east end of the choir, visible in the photo below. It was here that Becket’s shrine stood directly above his tomb in the crypt. William also designed the sexpartite vaulted roof, the ribs of which stand on columnar piers. True, the cathedral was extensively remodelled in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, under the sure guidance of Henry Yevele and Stephen Lote. Nevertheless, enough of William’s original design remains for the modern visitor to get a sense of his original vision.

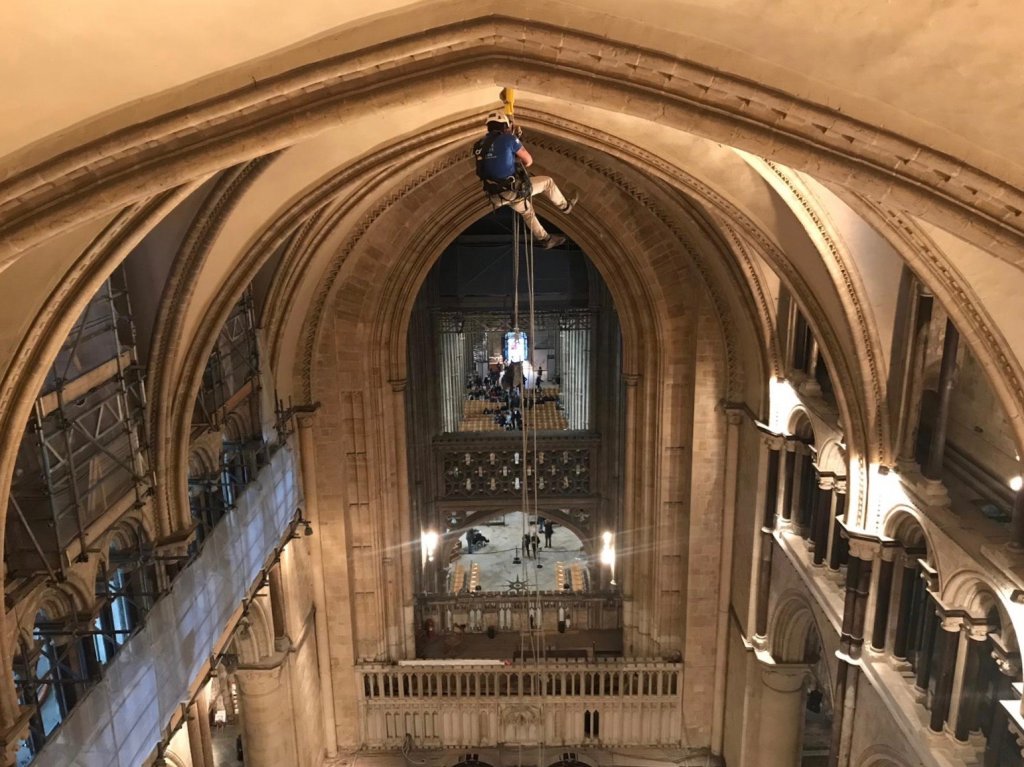

The stone walls of Canterbury Cathedral, its towers and pinnacles dominate the historic city. Stone is evidently a durable material with which to build. It is strong in compression and masonry buildings will usually remain stable as long as the ground conditions on which they stand remain stable. However, stone is also a natural material which, over time, wears away and suffers damage from the factors such as the weather and pollution. Historic buildings such as Canterbury Cathedral therefore require continual maintenance to preserve their fabric. Architects, archaeologists, conservators, surveyors and highly-trained specialist craftsmen and women, for example stonemasons, carpenters and roofers, all work together to maintain and preserve the fabric of the cathedral. In May 2019, I was fortunate enough to spend a day onsite with Richard Martin and Steve Smith from Heritage Stone Access, a company that specialises in inspecting, conserving and repairing the stone structures of historic buildings. In their jobs, Richard and Steve get to see buildings in ways that very few people do. For example, how many people have been fortunate enough to get as close as this to the cathedral’s rib vaulting since the time that it was built.

However, visitors to the cathedral do not need to abseil from the roof to see the ongoing process of repair and restoration. It is visible to anyone walking alongside the buttresses on the southern side of the nave.

These stones have deep alveolization. The damage caused to the original stones over the centuries was such that it was necessary to replace many of the stones entirely. I was surprised to learn from Richard that stones on the southern aspects of buildings usually suffer more from the effects of the weather than those on the northern sides. Not only do weather fronts in Britain tend to move in from the south-west, from which the northern sides of buildings are sheltered to a greater extent, but the sunshine on the southern aspects of buildings also take its toll on the fabric.

When the medieval cathedral was built, there would have been a masons’ lodge and a drawing office adjacent to the structure. It was here that William of Sens would have sketched out his plans for his team of workmen, it was here where templates would have been cut for each and every stone in the edifice. In many ways, little has changed for the modern restoration project. In the cathedral precincts, there is a workshop and a drawing office for the twenty-five or so stonemasons employed on site. It is here that the masons cut and shape the blocks of tone using hand tools. As we walked through this area I could see many of the stones laid out on pallets, ready to be moved to position, each one clearly marked so that the masons who set the stones into position know exactly where each one is to be placed. In this way, the moderns stonemasons use the same techniques as their medieval counterparts.

We ascended to the top of the scaffolding in the red hoist shown on the southern side of the cathedral.

The scaffolding itself is a remarkable structure. To construct a system such as this which allows simple and safe access to the cathedral while at the same time not damaging the fabric is a wonder. In 1178 William of Sens was unfortunately badly injured when some scaffolding collapsed causing him to fall fifty feet, forcing him to return to France. I tried to put all such thoughts out of my mind at the summit from where the view was pretty striking.

It is actually not surprising that the medieval scaffolding did collapse. The carpenters who raised it would have had to cut and prepare each piece of the wooden scaffold on site, continually working out how best to put up the structure and with only the power of man or beast to lift each piece into place. Considered in these terms, the achievements of the medieval carpenters actually seem all the more impressive.

The best view from the top of the scaffolding, however, was not of Canterbury spread out beneath us but of the cathedral in front and below us. From here, one can see the beauty and the grandeur of the fabric, but also the damage which it has suffered over the centuries. Much of the stone can, of course, be cleaned, restored and perhaps protected with a shelter coat without needing to be replaced. Some masonry, however, is quite simply beyond repair and, indeed, would be dangerous to leave in place. In this photo, for example, it is possible to see how the replacement masonry stands alongside the restored stone.

The amount of work involved in this project should not be underestimated. Each stone which is to be replaced has to be measured precisely in order to produce a template before it can be removed. Each replacement stone in this pinnacle was cut and shaped by hand from these templates. This one stone, for example, with its four decorative finials was carved from single block.

At times, it has been necessary to replace a whole series of stones, each of which had to be measured, templated and hand carved.

All the replacement stones are then set into place using a particular lime mortar. This is specialist work indeed. Medieval cathedrals were built by the most highly-skilled masons of the time. Their restoration today it is no different. Nine Anglican cathedrals have come together to form the Cathedrals Workshops’ Fellowship (CWF) to provide a training programme for apprentice stonemasons to develop the skills they need to become expert craftspeople. In many ways, the techniques used in the modern era are little changed from those of the Middle Ages. One place where this was most evident was in the restoration of the flying buttresses. When the cathedral was built, all the buttresses and arches would have been built over wooden centering which was then removed once the mortar had set. The masons working on replacing the buttresses today essentially use the same technology as their medieval forebears.

Of course, stonemasons are not the only craftspeople working hard to restore the cathedral. Indeed, the CWF also offers a training path for carpenters/joiners and electricians who wish to work on cathedral restoration projects. From the scaffolding, I actually looked down towards the newly-replaced roof of the cathedral’s nave, and could see the roofers replacing the lead at the western end of the cathedral.

The carpenters were working on hard on repairing the roof structure, in many cases working with original medieval beams.

The whole project is truly a team effort.

To this day the cathedrals of England invariably dominate and frequently represent the cities in which they stand. Canterbury’s delicate Gothic cathedral, Durham’s Romanesque brute basilica, York’s gigantic perpendicular Minster and Wren’s classical masterpiece in London all stand as unique symbols of their respective cities. They are fixed to their landscapes. But they are not inert or unchanging structures. They often took decades, if not centuries to complete, and their fabrics betray changing architectural fashions and techniques. They are living buildings. The restoration project at Canterbury Cathedral reminds us that buildings such as these will always require continuous maintenance. The evolution and development of the form of cathedrals mirrors the way in which their function has adapted over the centuries too. This is particularly true at Canterbury Cathedral. Of course, it remains primarily a place of worship and it continues to attract pilgrims and visitors. At the heart of the medieval cathedral, however, was the shrine to Becket. Indeed, the building was designed to stand as a glorious memorial to his memory. But in 1538 King Henry VIII (1509-47) suppressed Becket’s cult. His feast day was abrogated, all signs of Becket in London were taken down and one year later his image was removed from the city’s seal. At Canterbury, his shrine was destroyed. The modern visitor sees only a candle burning where it once stood. At the same time, the priory of Christ Church was surrendered to the king, and replaced with a college of secular canons. Yet out of the chaos of the Reformation, Canterbury Cathedral assumed a new role as the mother church of the Anglican communion, a communion which grew to be a global one in the following centuries. Today, together with St Augustine’s Abbey and St Martin’s Church in Canterbury, it forms part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. As both an institution and a structure, the cathedral has successfully adapted and renewed itself to survive and flourish in the world around it.

Further reading:

Nicola Coldstream, Medieval Architecture (Oxford, 2002).

Barnaby Thornton Lockyer

22nd January 2020 at 3:18 amI enjoyed reading your article and seeing the photos of restoration work and the views you had of the cathedral up high and the city below including the detail of new masonry. Thank you for sharing this account of your association with the restoration work. (You have an appropriate surname given your subject matter but I shouldn’t think for a moment that I am the first to remark on it).

Ian Stone

25th January 2020 at 1:59 pmThank you Barnaby. I was very lucky to go and see it.

Yes, there is an element of nominative determinism here isn’t there!