Samuel Pepys and the Plague of 1665

At the end of each month, Samuel Pepys, the great diarist, was wont to take stock of his affairs. Anyone who has read Pepys’s diary cannot help but be struck by his invariable cheerfulness on these occasions. His entry for 30 April 1665, 354 years ago today, was typical of the man: ‘thus I end the month: in great content as to my estate and gettings’. True, his responsibilities as Clerk of the Acts to the Navy Board and Treasurer of the Tangier Committee were causing him some concern, but Pepys was a hard-worker who was more than capable of dealing with whatever came his way in these roles. Besides, they were both lucrative appointments and the rewards justified his efforts. However, Pepys himself was unaware that it was his final reflection on the month that would prove to be the most significant. ‘Great fears of the Sickenesse here in the City, it being said that two or three houses are already shut up. God preserve us all.’

The ‘Sickenesse’ to which Pepys referred was, of course, the outbreak of pestilence that came to be known as the Great Plague. To be sure, plague had regularly visited London since its first recorded occurrence in 1348, during the course of which outbreak perhaps one-half of London’s population, feasibly as many as 50,000 people, died. The greatest mortality rate in sixteenth-century London was that of 1563, when 20,000 people, almost a quarter of the population, were wiped out. Approximately 85 per cent of the deaths in that year were a result of plague. In the seventeenth century, it is likely that London was free of the plague only in the years between 1612 and 1622 and the brief period 1627-29. Plague epidemics of 1603 and 1625 together were responsible for over 50,000 deaths. There was, then, nothing unusual about the appearance of ‘sickenesse’ in contemporary London and no reason for Pepys to believe that this year would be any worse than many others had been.

Indeed, the shutting up of houses mentioned by Pepys is evidence of one response which had been developed in London to outbreaks of the plague, namely quarantine. Attempts to confine households struck by plague can be seen as early as 1518, and in 1583 a set of plague regulations were drawn up which stipulated that all members of an infected household, whether sick or not, should be quarantined within their home for a month to prevent the disease spreading. There was clearly sense in this policy measure, but the problems with its enforcement are immediately obvious. In the first place, imposing a requirement such as this required manpower and money, neither of which the governors of the city of London had in abundance. True, London was easily the biggest and wealthiest city in the kingdom, but the Corporation of London had not yet put the structures in place to access more fully the city’s resources. Who would bring provisions to the incarcerated? Who would make sure that the infected were not leaving their houses? Indeed, it is a tenet of Christian belief that it is an act of charity to care for the sick, so who would ensure that healthy friends and neighbours were not also visiting those struck by the plague? There can be no doubt that this sort of thing happened commonly enough. One would have to have a heart of stone not to be moved by one particular instance of a breach of quarantine recounted by Pepys on 3 September. A saddler and his family in London had been struck by plague and the husband and wife had buried all their children apart from one ‘little child’. They had now been confined to their house and ‘did despair of escaping’. However, they still wanted to save the life of the last remaining child, and therefore they ‘prevailed to have it [the child] received stark naked into the arms of a friend, who brought it (having put it into new fresh clothes) to Greenwich.’ Pepys and others of the parish vestry agreed that the child could, on this occasion, remain in Greenwich. This was clearly a breach of the quarantine requirements yet also a merciful display of humanity on their part.

The second obvious problem with quarantining healthy citizens with the sick was the understandable reluctance of many of the healthy to be confined with the ill. In fact, many believed, perhaps rightly, that a measure such as this guaranteed only to increase the number of Londoners falling victim to the plague. Whether that was the case or not, how many of us would agree to be incarcerated with someone struck by a probably-fatal disease, whose transmission we understood hardly at all? To be sure, many Londoners did visit and care for plague victims in the summer of 1665, but many of the sick were shunned, made homeless by their masters and or/landlords, or even paid by parish authorities to leave the parish.

Simply put, the authorities in London had not the infrastructure in place to cope with epidemic outbreaks of plague. The constables and watchmen of London were too few in number to be genuinely effective in patrolling quarantine. There was no one body ultimately responsible for the prevention of disease in London. There were not enough doctors and no one really understood how the disease travelled anyway. Perhaps the best response would have been to move the sick into pesthouses, but by 1665 only five of these existed and they could care for barely more than 500 people. In fact, much of the responsibility for caring for the sick was entrusted to the parishes of London. True, the parishes were the institution of government closest to the Londoners and therefore they were well placed to deal with the plague’s effects. But the poorer parishes, usually those in the suburbs, not only had fewer resources on which to call when plague struck, they were also faced with the problem that plague struck greater numbers of poorer Londoners than it did their richer fellows.

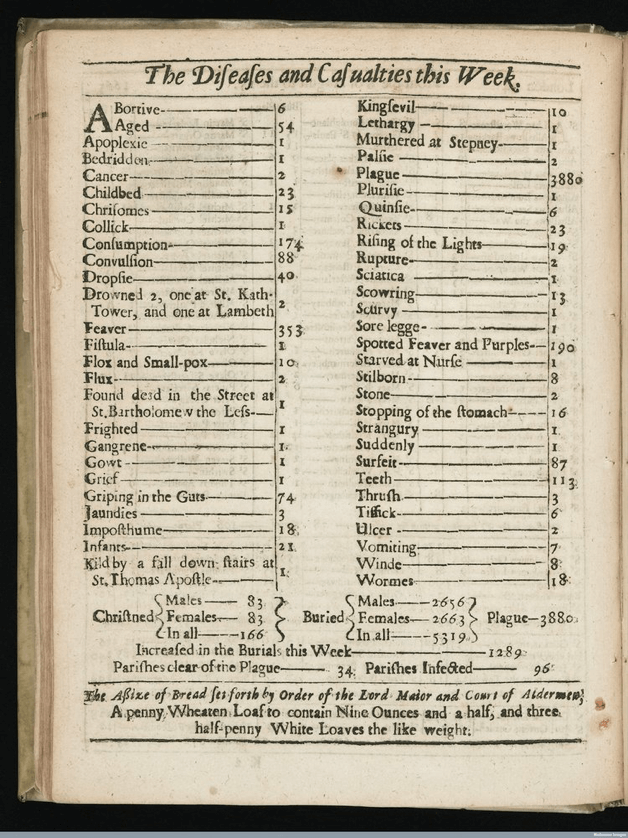

Even had there been better infrastructure in place, it is still likely that the city would have been overwhelmed by the virulence of the plague that year. According to the contemporary weekly bills of mortality, in 1665 more than 80,000 Londoners died, three-quarters of whom were killed by the plague. That is to say, perhaps as many as 20 per cent of the city’s population. Were the same proportion of Londoners to die in this age, we would be thinking of around 2 million deaths, an unimaginable comparison. When thought of in these terms it is a wonder that the social order did not collapse completely. The effects of the plague would actually have been felt much more dramatically than this. First, plague was to all intents and purposes a summer visitor to London. 70,000 of the 80,000 deaths in London in 1665 were recorded in just three months from August to October. Second, the true numbers were probably even higher than the official figures allow. Pepys himself noted, on 31 August, the ‘sadder and sadder news of its [the plague’s] encrease. In the City died this week 7496, and of them 6102 of the plague. But it is feared that the true number of the dead this week is near 10000 – partly from the poor that cannot be taken notice of through the greatness of their number, and partly from the Quakers and others that will not have any bell ring for them.’

One would have expected that the extent of the suffering in London displaced even Pepys’s legendary cheeriness. There can be little doubt that Pepys was greatly affected by what he saw that summer in the city. On 7 June he saw, for the first time with his own eyes, ‘the sad sight’ of several houses in London with a red cross and the injunction ‘Lord have mercy upon us’ painted upon their doors. On 8 August he lamented, on a visit to the west of the city, that ‘the streets [were] mighty empty all the way now, even in London’. On 7 September he received the weekly bill of mortality, which showed that almost 7000 Londoners had died of plague, ‘which is a most dreadfull Number – and shows reason to fear that plague hath got that hold that it will yet continue among us.’ Perhaps most evocative is his entry for 14 September, where we read of the deaths from plague of several people close to Pepys and his own daily encounters with the effects wrought by plague on the city.

Yet, even surrounded by such sorrow, it is time and again Pepys’s happiness which is most striking to the reader of his diary. A wedding at the end of July rounded off what had been a splendid month for Pepys, abounding in ‘joy and humour, and pleasant Journys and brave entertainments’. Pepys admitted that August ended with ‘great sadness upon the public through the greatness of the plague, everywhere through the Kingdom almost’, but went on to write that ‘as to myself, I am very well; only in fear of the plague’. On 30 September he wrote that ‘I do end this month with the greatest content, and may say that these last three months, for joy, health and profit, have been much the greatest that ever I received in all my life in any twelve months almost in my life – having nothing upon me but the consideration of the sickliness of the season during this great plague to mortify mee. For all which, the Lord God be praised.’

Pepys’s account of summer of 1665, when London was ravaged by plague, is just one part of his voluminous (1.25m words), incomparable and evocative diary. One of the things which most strikes me about Pepys is how directly he speaks to us in his diary and thus how human he appears. There is no reason at all to doubt that he was as cheerful as he appears in the pages of his diary; Pepys was, after all, a brutally honest self-critic. It might, at first, seem incongruous that someone could remain so happy in the middle of such suffering, but Pepys had reason enough to be satisfied with his lot. In the midst of death, he was in life.

Ann Walker

1st May 2019 at 1:12 pmThis blog brings home the reality of endemic and epidemic disease-terrifying and unavoidable. I hadn’t realised that few years were without a plague outbreak. The logistics of dealing with huge numbers of deaths, especially infected bodies, is unimaginable and I wonder how we would deal with such an emergency now (2 million Londoners!). I have read a version of Samuel’s diary but this article certainly broadens my view of London life – I have previously been more interested in his descriptions of his own life. Thanks, Ian

Ann

Ian Stone

1st May 2019 at 3:01 pmThank you Ann. Yes, 2m Londoners is a frightening comparison isn’t it? You’re quite right too about the value of Pepys too. We can use him in so many ways.

Judy Darby

27th June 2019 at 11:00 amFascinating and chilling. All those who would like to live in a ‘more romantic era’ should read this.

Ian Stone

28th June 2019 at 9:39 amYes, it certainly was a terrible time in London’s history. We all focus on the Plague of 1665 too, but it was a terrible and regular visitor to London for 300 years, often carrying off thousands of people each time. It is, though, always nice to remember Pepys I find. In the middle of all this suffering he is so full of life and honesty.

Ian Stone, historian | Finding the Traces of London’s Huguenots

28th October 2019 at 10:10 pm[…] Samuel Pepys and the Plague of 1665 […]

Elizabeth Lewis

25th May 2020 at 9:19 amGreat really interesting …and that moving story about the last remaining child ,! Superb blog ..thank you ian stone

Ian Stone

25th May 2020 at 9:46 amThank you Elizabeth. Pepys really is incomparable isn’t he? We’re so lucky to have him