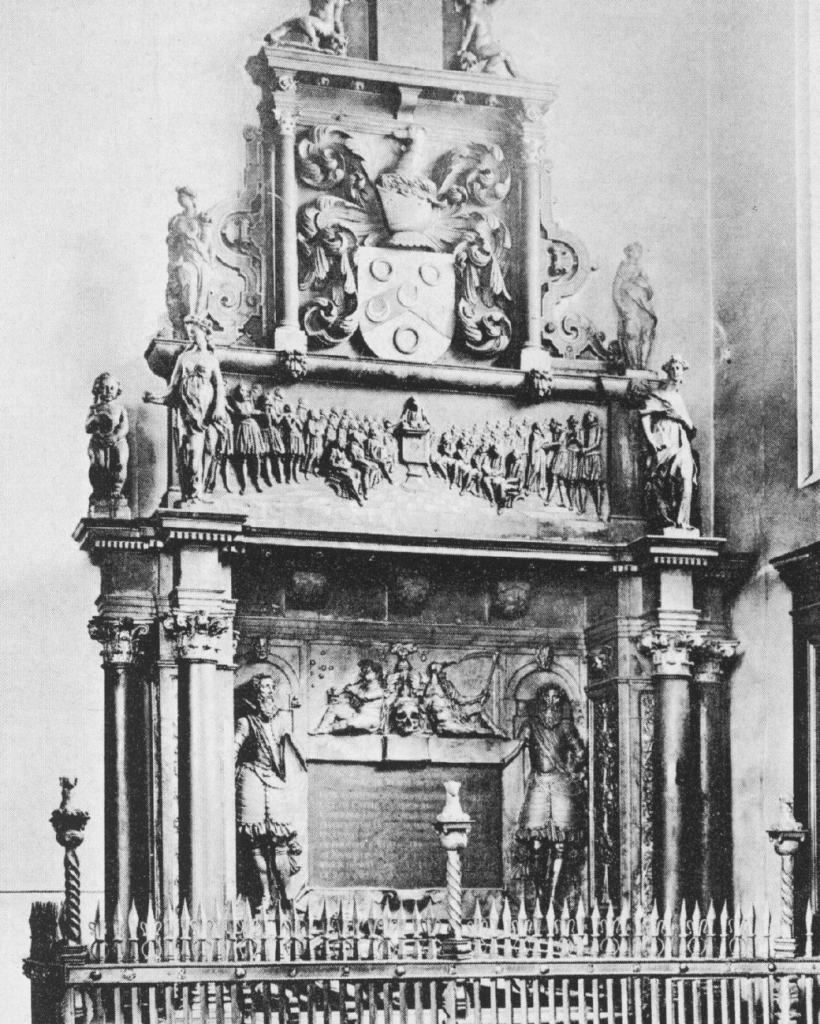

The Thomas Sutton Memorial in Charterhouse Chapel

There is an extraordinary memorial to Thomas Sutton (1532-1611) in the Charterhouse Chapel at Smithfield in London. Standing twenty-five feet high, and thirteen feet wide, it dominates the north aisle of the Chapel. Sutton founded the Charterhouse in 1611 as both a school and as an almshouse and hospital for up to eighty inmates. While the school has moved to Surrey, the almshouse remains and its residents are known as ‘brothers’, whether they are male or female. The use of the term ‘brothers’ reminds us that the original building on the site of the Charterhouse was a Carthusian monastery. The monastery was built in 1371 and the Carthusians, generally, lived simple, peaceful and frugal lives, for which they were liked and admired by medieval Londoners. At the time of the Dissolution, the monks of the Charterhouse offered some of the most obdurate resistance to Henry VIII; in 1535 several monks were hanged, drawn and quartered for refusing to take the king’s Oath of Supremacy. Indeed, on 4 May 1535, two months before his own execution, Thomas More watched as four monks left the Tower of London to be taken across the city to the put to death at Tyburn. Just over three years later, in November 1538, the monastery was suppressed.

Many contemporary religious reformers hoped to see the property and wealth of the suppressed and dissolved monasteries put to use relieving the poor, aged and infirm. To an extent this did happen. By the end of the reign of King Edward VI (1547-53), there were five hospitals under secular control in London. The medieval hospitals of St Bartholomew’s and St Thomas’s were refounded, in 1546 and 1551 respectively, to care for the sick and feeble; Christ’s Hospital for orphans, and Bridewell as a house of correction for the disorderly poor and vagrants, were both established in 1551; and the medieval house of St Mary Bethlehem was refounded in 1547 as the Hospital of Bethlem, aka Bedlam, for the mentally infirm. But much of the property, including the Charterhouse, found its way into the hands of wealthy nobles and gentlemen. At the end of the sixteenth century, the Charterhouse was the London house of Thomas Howard, earl of Suffolk. On 9 March 1611, Suffolk sold the Charterhouse to Thomas Sutton for the handsome sum of £13,000.

Sutton had long desired to found a hospital and he now had a suitable building. However, he was nearly eighty years old and he had only months to live. Fortunately, he was able to establish the foundation before he died on 12 December 1611. Sutton was buried in the new Charterhouse Chapel which stands, more or less, on the site of the old Carthusian chapter house. It was built in 1613-14 by Francis Carter, a carpenter by training, who held an official position as Chief Clerk of the King’s Works from 1614 until his death in 1630. In his twenty-three-page will Sutton gave generously to several charitable causes. But the amounts involved in these bequests were dwarfed by the enormous sum of £50,000 he left to his new hospital. How had Sutton acquired such wealth? His origins were humble, but he enjoyed a successful early career serving Queen Elizabeth I (1558-1603) and various aristocratic patrons for which he was well rewarded. He was, too, a sharp businessman, who accrued a significant fortune acquiring properties and lending money. Simply put, he was one of the men ambitious and capable enough to capitalise on the opportunities available in the second half of the sixteenth century.

For his munificence Sutton was hailed as a hero by many contemporaries, especially the Protestant clergy who used him as an example to refute criticism that the new Protestant religion had not done as much for charity as the pre-reformed faith had done. In November 1615, the mural monument to Sutton in the Charterhouse Chapel was completed at a cost of £400. Sutton’s memorial was created by three men who described themselves as ‘citizens and freemasons of London’, Nicholas Stone (no relation to me), Edmund Kinsman, and Nicholas Jansen.

By far the most famous of these three men was Nicholas Stone. He had only returned to London from Holland in 1613, where he had worked with Hendrik de Keyser, master mason to the City of Amsterdam, and married de Keyser’s daughter, Mary. Stone was one of the leading sculptors, master masons and architects of his day. As a mason and architect he worked with Inigo Jones, Surveyor-General of the King’s Works, on the Banqueting House in Whitehall (1619 to 1622), as well as to his own designs at a chapel containing the memorial to Lady Digges at Chilham in Kent (1631-2), on Cornbury House in Oxfordshire (1631-3), Goldsmiths’ Hall in the City of London (1635-8), Kirby Hall in Northamptonshire (1638-40), Balls Park in Hertfordshire (1638-40) and on Lindsey House in Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London (c.1640). His output as a monumental sculptor was prodigious and there are simply too many works to list here. Among the most famous of his memorial works include the monuments to Henry Howard, ninth earl of Northampton in Trinity Hospital, Greenwich (1615-16), John Donne in St Paul’s Cathedral, London (1631-2), and John and Thomas Lyttleton’s effigies in Magdalen College Chapel, Oxford (1635). Stone’s reputation was so high that he was given official positions in the royal office of works, first as ‘Master Mason and Architect’ at Windsor Castle in 1626, and then as Master Mason to the Crown in 1632. He died on 24 August 1647 and was buried in St Martin-in-the-Fields, Westminster, where a memorial (now destroyed) remembered his ‘knowledge in sculpture and architecture’. Stone was, according to Sir John Summerson, one of only three men employed in the royal office of works under Inigo Jones who could in any way be called ‘architects’. One of the other men was Francis Carter, designer of the Charterhouse Chapel.

In his surviving note book, Stone tells us that he was responsible for ‘all the carven work of Mr Sottons tombe.’ It was carved early in Stone’s career and, as a whole, it is not one of his most sophisticated nor refined pieces. It is, to my mind, somewhat heavy and unbalanced. Feel free to disagree with me on this, however, in the comments section below. Nevertheless, it is still a remarkable piece. Immediately obvious are the four black marble Corinthian columns supporting a trabeated canopy. Underneath this canopy, and somewhat more difficult to see, is an alabaster effigy of Thomas Sutton. He is clothed in a doublet and a fur-lined robe. He faces east, in expectation of resurrection and his hands are clasped together in prayer.

Above the effigy on the wall is a black marble inscription-tablet which remembers Sutton. The tablet is supported by two figures who probably represent soldiers, and therefore Sutton’s early military career. Above this tablet is a representation of mortality: two figures, one either a youth blowing bubbles or Vanitaswasting time and energy on trivialities, and the other Time with his scythe, seated either side of an hour-glass placed atop a skull. Above the canopy is a wonderfully detailed relief panel, shown below, which shows a preacher (Sutton? The master of the Charterhouse?) expounding the Word to forty brothers of the Charterhouse.

The brothers listen intently while various gentlemen, representing Sutton’s trustees and the governors of his foundation, flank the congregation. To the left of this relief panel stands a female figure representing Hope and a boy (with a gravedigger’s shovel) representing Labour; to the right a female figure represents Faith and a boy Rest. Intriguingly, in a black and white photograph of the memorial reproduced in W.L. Spiers’ edition of Stone’s note book and account book in 1918-19 (plate III), the female figures stand in front of the boys, whereas today the boys stand on the front columns.

Perhaps this happened when the Chapel was restored after it was damaged by enemy action in World War II? Please do comment below if you can shed any light on this change. Four more black marble columns stand above the relief panel, either side of an achievement of arms, supporting an entablature. To the left of the arms stands Wealth, to the right Piety, and at the summit of the whole memorial a representation of Charity. These five allegorical female figures were chosen by the governors of the foundation to represent best Sutton’s establishment of the Charterhouse.

Sutton deserves to be remembered for his extraordinary bequest. More than four hundred years after his death, Sutton’s generosity continues to provide support in the way which he originally intended. His memorial was made by Nicholas Stone, one of the finest sculptors to work in seventeenth-century London. It is found in Francis Carter’s mannerist Chapel, which stands on a site where there has been Christian worship, more or less continuously, for almost 650 years. A visit to see Sutton’s memorial has something to offer anyone with an interest in London’s history.

Further reading:

W.L. Spiers (ed.), The Note-Book and Account-Book of Nicholas Stone, Walpole Soc., vii, (1918-19).

‘Nicholas Stone’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

sarah lennard-brown

20th March 2019 at 4:41 pmLovely to read such an interesting blog about both Sutton and – the appropriately named Mr Stone 🙂

Ian Stone

21st March 2019 at 1:17 pmThank you for helping me with the hospitals of early modern London Sarah

Ian Stone

7th July 2019 at 9:33 amJames Spellane, one of the Visitor Hosts at the Charterhouse, was kind enough to send me a copy of the English Heritage Survey of London from 2010. From this, I have learnt that the female figures of Faith and Hope wee swapped with the cherubs representing Labour and Rest in 1951, the the monument was restored by Cecil Thomas.